A Renaissance Master: Michele Da Verona's Battle Scene Elizabeth Siddiqui - 05/10/2023

From trade and unconventional political systems, Northern Italy grew economically prosperous during the 15th and 16th Centuries allowing the arts to flourish as they led the European Renaissance. With patrons being exceedingly wealthy, art during the Italian Renaissance was intrinsically tied to money and status and would often depict the systems that made such patrons successful, such as marriage and trade. Marriage during the Renaissance, especially amongst the upper class, was a business transaction and exchange of wealth between two families, with love and desire factoring very little into most marriages. The transactional nature of elite Renaissance marriages made the visual representation of the economic exchange utmostly important; therefore, a large portion of Renaissance art concerns marriages and betrothals. Amongst a women’s dowry would often be precious fabrics, jewels, metal objects, and furniture that would be carried in a cassoni during the nuptial process. A cassoni was a chest and seat elaborately decorated in painting or engraved metal and commissioned by the groom. Through their role in the nuptial process and position next to the marriage bed, these cassonis were a physical representation of the economic blending of marriage and the significance of art in the public and private lives of wealthy Italians. Typically, episodes from classical or biblical history and mythology, positive narratives for a new couple, decorated these chests; however, they were occasionally adorned with battle scenes or more violent subject matter.

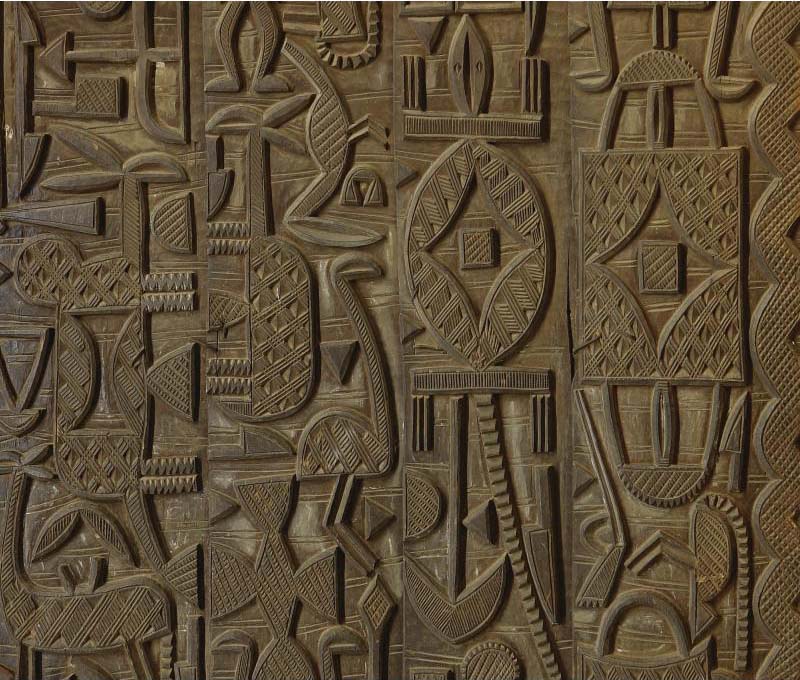

Framed by cliffs and trees, this battle is fought on an open field. The different positions and poses of the soldiers and horses create a three dimensional composition, and the horses and soldiers being higher in the painting creates a linear perspective. The smoothness of the figures and their illumination by light are emblematic of Michele de Verona’s technique. With the two armies slightly angled towards each other, two figures on horseback–one with a white cap and his arm raised back with a sword in profile and the other in a contrapposto pose–with a flag flying directly overhead are the focal point of the painting, as all perspective leads towards them. The muscularity of the horses, many of them with their front legs raised, is accomplished through chiaroscuro and shading that became a Renaissance staple. Furthermore, the contrapposto and dynamic poses of many of the soldiers provide movement to the painting and reflect the Renaissance obsession with human form after the discovery of many Greek and Roman statues that they attempted to replicate.

Michele da Verona (1470-1540) was a Renaissance master greatly influenced by the Venetian school of painting. He was a contemporary of Paolo Morando Cavazzolo–he may have even assisted Cavazzolo with the decorative works of San Bernardino–and is known for his Crucifixion in the Refectory of San Giorgio in Verona and several pieces in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. His tempera Battle Scene on the panel was in the tempera technique–the oldest method of painting, and very widespread during the Renaissance, in which pigment was mixed with a water and egg solution–and originally decorated a cassoni but was subsequently removed and sold or gifted as a sole panel. The painting was a gift to Thomas Bailey Aldrich from the actor Edwin Booth (1833-1893) in the mid-late 19th century, who possessed it by descent. It also bears the Colnaghi label on the back of the painting–one of the most established art galleries for Old Master paintings in the world.

With bright pigment, tight composition, and mastery in movement and form, Michele da Verona’s Battle Scene is a fine example of a Renaissance painting of museum quality.

Bibliography:

Bayer, Andrea, ed. Art and Love in the Renaissance Italy. New York, NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2009.

Leave a comment