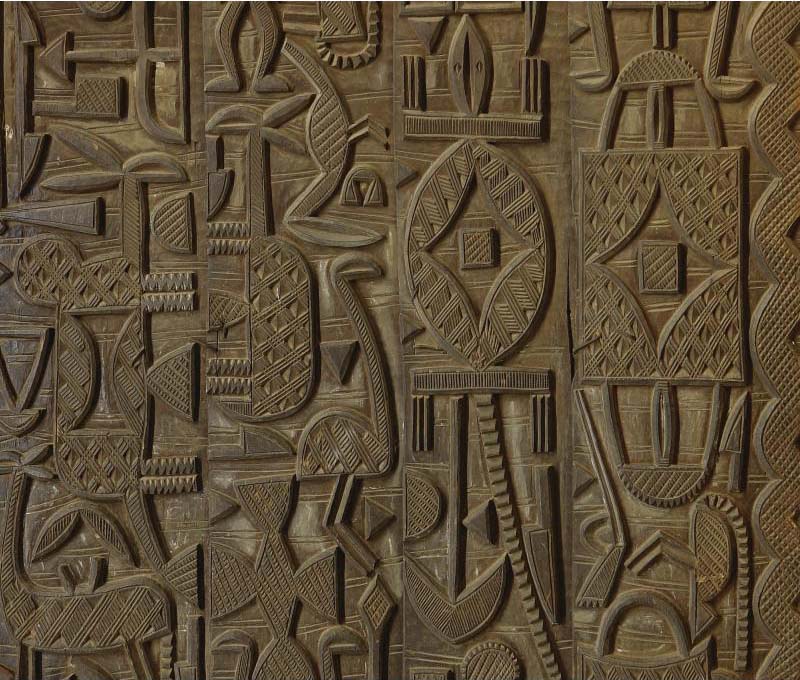

Maya Polychrome Vessel depicting a youthful Maize God

Images of the young maize god are among the most common in Mayan art, especially in ceramics, which were apparently designed (whatever their day-to-day use) as funerary offerings.

This ceramic is remarkable both for its shape and for the virtuosity its treatment of a common theme. The young maize god offers a cache plate of tamales to the dead. The setting is Xibalba. The smoking ahau scrolls surrounding the god (see Schele and Miller 1986:287, plate 116) may imply the high status of the dead owner. The abundance of the tamales, which are seen end to end in the same way that codices are seen end to end in the Princeton Vase (Schele and Miller 1986:286, 296, plate 115; Coe and Kerr 1998:110, fig.84) and elsewhere (Coe and Kerr 1998:88, Schele and Miller 1986:52, fig 39), emphasizes the votive function of the vessel, whose in the tomb is also implied by the cache plate’s kimi glyph (the emblem of death; see Kerr 1390 and Kerr 4651) and other tamale emblems that float in supernatural space around the god.

The modern interpretation of Mayan emblems is complicated by their visual synesthesia. Here, for example, the blood beads that ornament the smoke scrolls of the ahau emblems, with the blood scroll iconography of the god’s frontal headdress, may evoke the k’ulel scrolls emblematic of the life spirit (Schele and Mathews 1998:112) as well as the jester god headband, a personified royal headdress (Schele and Mathews 1998:412) cognate with the ahau emblem, “lord.” Some of the blood beads, moreover, especially on one side, are double concentric circles in which the inner disk is open. A death eye (see Schele and Miller 1986:53, fig 45; Robicsek and Hales 1981:22, vessel 21) with a blank pupil would have this form. The glyphic function of these beads or eyes may be to tell the viewer that the scene is the underworld, and the occasion the nourishment of the dead under perpetual threat from the death gods invisible around the margins of the scene.

The two figures of the maize god are remarkable not only for the virtuosity of their rendering but for their differences. Both their bodies are well nourished. Their arms and thighs are covered with framed oval cartouches. The formal emblem of the god’s mirror mark is a blank framed cartouche split by a double line (Schele and Miller 1986:43, fig 20, and 53). This mark is emblematic of an obsidian mirror. Its best known association is with images of K’awil, or God K, who carries an obsidian mirror in his forehead that is pierced by a smoking ax.The simpler markings on our ceramic may be a synesthetic formula for the more elaborate markings of a codex vase painted with a finer brush.

Side A offers a god with a smooth forehead and a flowing profile. Side B offers a god with a broken profile and a narrow head. If Mayan ceramics had to be painted quickly, before crucial elements of the paint dried, these differences could be explained by the artist’s need to work faster on the second side than the first. Both sides offer the sure, flawless virtuosity of an experienced hand.The god’s heads taper to a narrow bulb framed by a tassel that resembles the tassel of an ear of corn. Though a tapered skull is typical of Mayan imagery, and may merely reflect cranial deformation and the use of cradle boards for carrying babies, the tassels here reveal the identity of the god.

The expressions of the faces are reverent and serene.

The plates of tamales the gods present are the double lozenges characteristic of late Classic Mayan renderings of cache plates (see Schele and Mathews 1998:50, fig.1.24). The cache plate on side A carries the glyph for kimi, death, that Schele and Mathews (1998:113 and fig 3.18) illustrate from the sarcophagus lid of Hanab-Pakal’s tomb in the Temple of the Inscriptions at Palenque, where it forms part of the portal imagery of the quadripartite god’s personified offering plate.

Commentaries on the maize god do not typically say so, but mythological sources (eg, the PopolVuh) make it clear that there were originally two maize gods, who thus prefigure the twinning of the heroes who saved them. The images here, however, painted quite differently though obviously by the same hand, may well be of the two original gods whose noisy ball game led to so much trouble with the lords of the underworld.

The Paste

A moderately coarse gray brown Mayan buff ware

The Slip

A thin white layer darkened by numerous small blooms of manganese dioxide

The Surface

Glazed throughout with the characteristic dull gleam of Peten gloss, a polish whose origin and mode of application are unknown, but are not those of a conventional ceramic glaze

The Form

Schele and Mathews 1998:76-77, fig 2.16) illustrate an Ik ceramic (Kerr 1453) that portrays a gourd vessel with the same barrel shape as our ceramic. If our vase originally had a stem lid like the vessel illustrated, it would have resembled that vessel quite closely except for size. The barrel is a rare shape in Mayan ceramics, but Sotheby’s (November 22, 1999, lot 69) illustrates an incised Late Classic orange ware vessel of similar form.

The Decoration

The seated image of Hun Hun Apu, the young maize god, offers a plate of tamales, behind him a multicolored feathered backrack, the smoking ahau symbol framing the scene, the god’s headdress including a frontal scrolling banner evoking the jester god headband and k’ulel scroll.

The Style

Possibly a regional variant of the Late Classic Ik style

The Condition

Intact, with two vertical cracks at the rim and some infilling of details in red paint, each infill about l cm in size, where the haze of superficial scratches characteristic of Mayan ceramics has penetrated the red paint to the white slip.

References

Justin Kerr, Maya Vase Database, mayavase.com on line

Linda Schele and Peter Matthews, The Code of Kings, Scribner 1998

Linda Schele and Mary Miller, The Blood of Kings, Braziller 1986

Francis Robicsek and Donald Hales, The Maya Book of the Dead, University of Virginia Art Museum 1981

Michael Coe and Justin Kerr, The Art of the Maya Scribe, Abrams 1998

Leave a comment